Today OEP is releasing the findings from the 2021 Arkansas Student Discipline Report. We identify trends and a number of key student outcomes related to student discipline in the Arkansas public schools, and examine how recent policy changes are working.

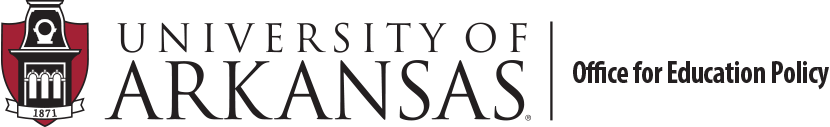

These past two years have been very different, and the data reflect sharp declines in reported student discipline incidents and associated consequences. Reported incidents in 2020-21 were down more than 60% compared to 2018-19 rates. While we cannot say for certain, this is likely the result of COVID-related school closures and modifications to school settings (i.e. fewer kids in the lunchroom at one time). We cannot tell if the decline is the result of improved student behavior or inconsistent reporting by schools. We recommend reading the full report, but we wanted to share the highlights of what we found.

How did COVID change reported student discipline infractions?

- There was a large decline in the number of reported student disciplinary infractions in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years. While we cannot say for certain, this is likely the result of COVID-related school closures and modifications to school settings (i.e. fewer kids in the lunchroom at one time). We cannot tell if the decline is the result of improved student behavior or inconsistent reporting by schools. There were some schools that simply did not report any disciplinary incidents in 2019-20 or 2020-21: 63 schools in 2020-21 and 36 schools in 2019-20 that had previously reported incidents did not report a single one. The lack of reporting by these schools, however, cannot fully explain the sharp decline in reported student infractions in these last two years.

How have reported student infractions and associated consequences changed over time?

Infractions

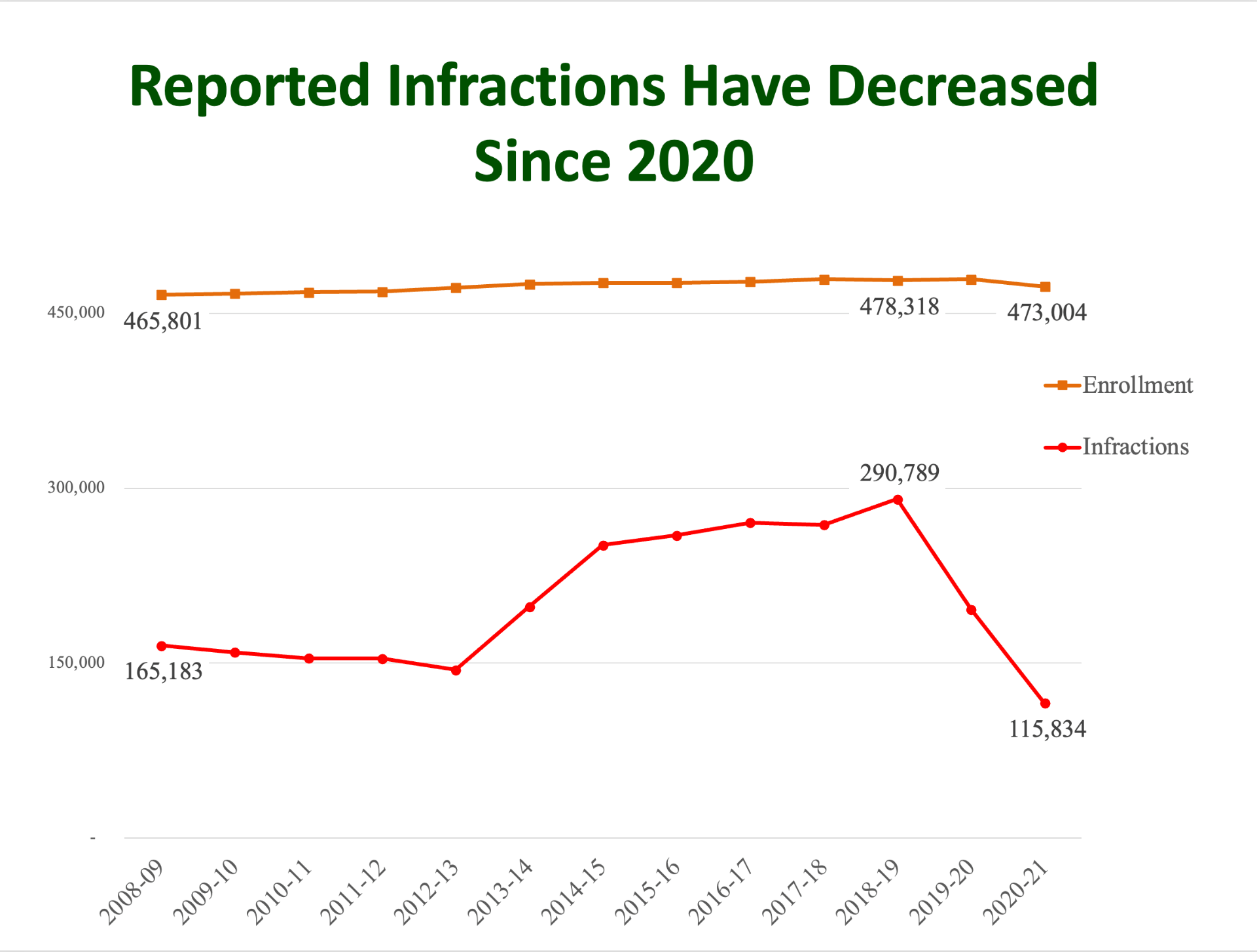

- Prior to COVID-19-affected school years, the number of disciplinary infractions nearly doubled: from approximately 165,000 incidents in 2008-09 to approximately 291,000 in 2018-19. It is unlikely that this increase in referrals was due solely to increases in misbehavior over time. In particular, given that the largest growth was in the category of “other” non-specified infractions, which are relatively minor compared to other categories – this increase may reflect at least in part an increased focus on reporting more minor disciplinary incidents.

- Approximately 80% of discipline referrals reported over the past 14 years are for disorderly conduct, insubordination, or “other” non-specified infractions, indicating that the vast majority of reported infractions are relatively subjective.

Consequences

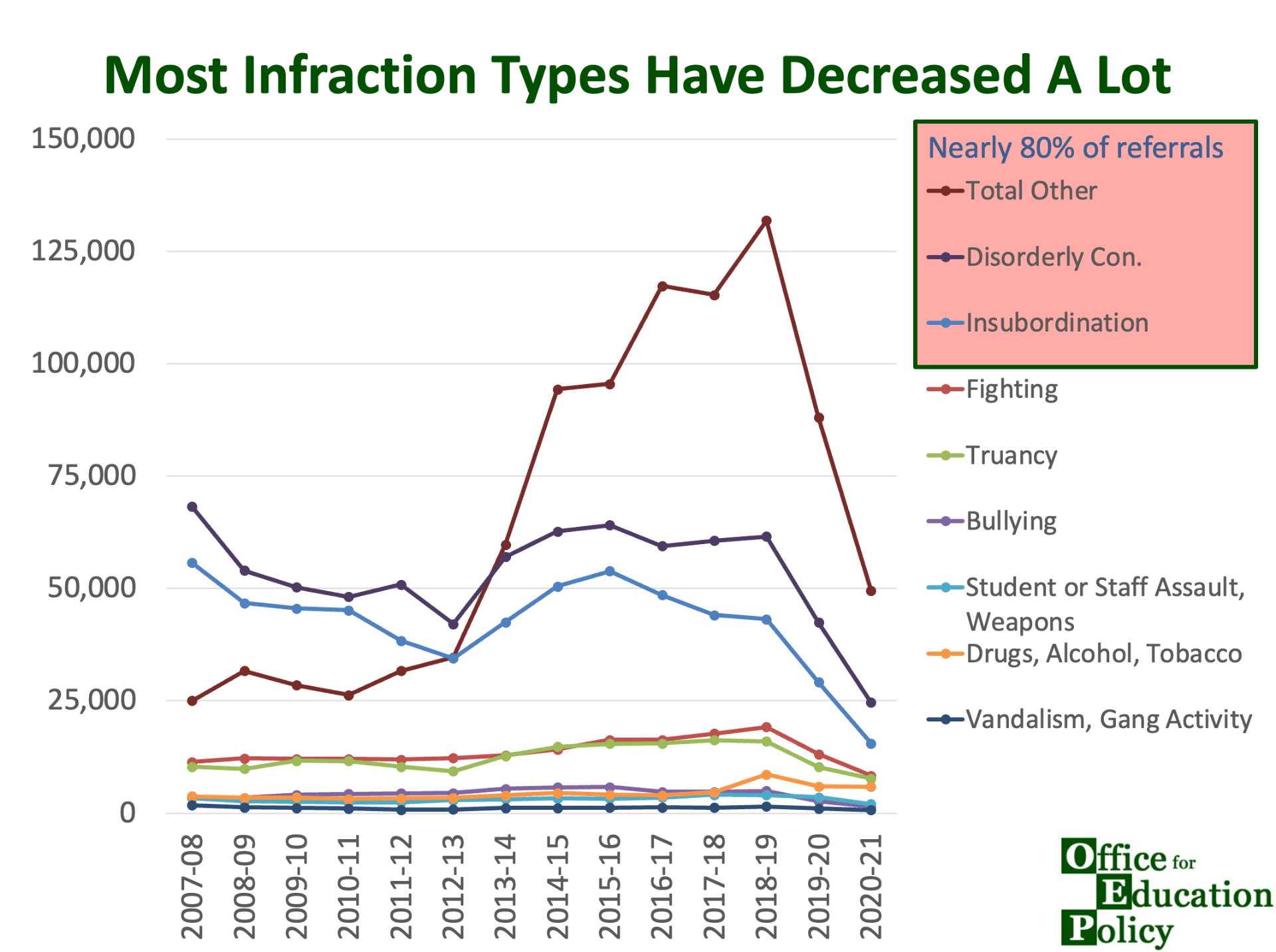

- There has been a decline in reliance on OSS and corporal punishment over time. The use of OSS as a consequence declined from 22% in 2008-09 to 15% in 2020-21. Corporal punishment was used a consequence for 16% of infractions in 2008-09 and declined to being used in 3% of infractions in 2020-21.

- The most common consequences are “other” non-specified consequences (45%) in-school suspension (ISS, 36%), and out-of-school suspension (OSS, 19%).

- Excluding the new reporting categories added in 2016-17 (detention, warning, Saturday School, bus suspension, and parent conference), the percentage of “other” drops to 23%. Further investigation and/or more detailed reporting of what is included within the “other” consequences would be useful for understanding whether this represents a meaningful change for students.

Are there racial/ethnic or programmatic (free/reduced lunch or special education) disproportionalities in school discipline?

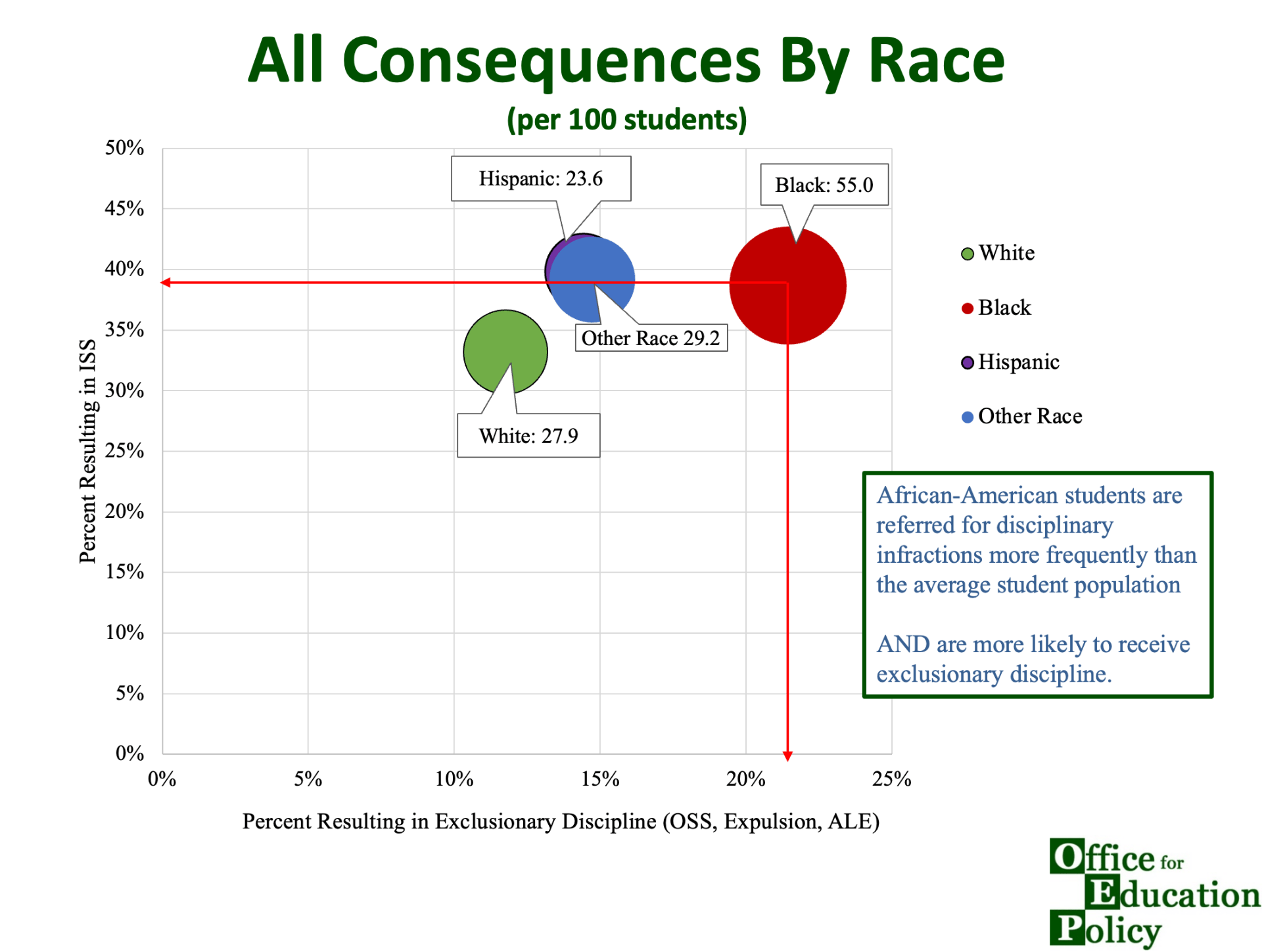

- Unfortunately, yes. As we have consistently reported, disproportionalities by race/ethnicity, free- and reduced- price lunch eligibility, and special education status exist both in terms of the number of referrals for infractions of various types, as well as in the likelihood of receiving exclusionary discipline, conditional on referral for a particular type of infraction. For example, Black students received about 119.8 referrals per 100 students per year, during the last two years prior to COVID, and about 55 referrals per 100 students per year during the two recent COVID-affected years. This is relative to only 43.5 referrals and 27.9 referrals per 100 White students, respectively, during the same time periods. Notably, these disproportionalities are largely driven by larger numbers of subjective infractions such as disorderly conduct, insubordination, and “other.”

- Then, conditional on being written up for any infraction, Black students receive OSS, expulsions, or referrals to ALE at higher rates than other groups. In 2017-18 and 2018-19, approximately 23% of all infractions for Black students resulted in exclusionary discipline, relative to only 13% for White students, 14% for Hispanic students, and 16% for students of other races. The exclusionary rate decreased slightly in 2019-20 and 2020-21 to 21% of infractions for Black students, but remained high relative to other groups. Thus, Black students in the state are overrepresented both in terms of referrals, and in terms of exclusionary discipline conditional on a referral.

To what extent are schools complying with Act 1059 of 2017, which limits the use of OSS and expulsion for students in kindergarten through fifth grade?

Act 1059 restricted the use of OSS and expulsion for K-5 students except when a student’s behavior: a) poses a physical risk to himself or herself or to others or b) causes a serious disruption that cannot be addressed through other means.

- OSS and expulsions in grades K-5 have declined steadily since this law was passed, from over 13,000 incidents in 2016-17 to roughly 9,000 in 2018-19. Reports were even lower in 2019-20 and 2020-21, but are at least partially impacted by COVID-19 related school closures, so we cannot conclude that these more recent declines indicate greater compliance with the policy.

- In the past six years, K-5 students were most commonly suspended or expelled for disorderly conduct (31% of K-5 OSS and expulsions), “other” infractions (21%), fighting (20%), and insubordination (12%).

- Reliance on OSS and expulsion in response to elementary grade referrals has declined over time, primarily offset by increases in “other” consequences. These declines in reliance on OSS and expulsion were primarily due to declines in the use of these consequences in response to “other” non-specified infractions, disorderly conduct, and insubordination.

- The count of OSS and suspensions in grades K-5 decreased for most racial/ethnic groups, with very large declines during the COVID-affected years. All racial/ethnic groups except for Asian students and students of two more races also experienced declines by the 2018-19 school year (pre-COVID).

- The share of K-5 students receiving at least one OSS or expulsion, however, did not decline as much, suggesting that much of the reduction was due to reductions in multiple infractions, rather than reductions in the share of individual students who received OSS or expulsion. For example, from 2015-16 to 2018-19, the share of Black students in grades K-5 receiving at least one OSS or expulsion only declined from 9.1% to 8.2%. The corresponding share for White students remained fairly stable over this time period, only decreasing from 1.9% to 1.8%.

- Along elementary schoolers, Black students in particular are at a high risk of OSS and expulsion. They were nearly five times as likely to receive at least one OSS or expulsion in 2015-16, and remain over 4.1 times as likely in 2019-20 and 2.5 times as likely in 2020-21, despite the COVID-19 related declines in disciplinary reports.

Are schools complying with Act 1329 of 2013, which bans the use of OSS as a legal disciplinary response to truancy?

- The state is making good progress; use of OSS for truancy declined from about 14% of all truancy cases in 2012-13 to about 1% of cases in 2020-21.

We can see that the common-sense ban on using OSS as a consequence for truancy has largely been adopted by school districts throughout the state, and that exclusionary discipline has dropped for elementary students since 2017. It is important that schools continue to report discipline incidents and associated consequences, so that we have the information needed to identify other opportunities to support Arkansas students through policy changes.

Despite declines in counts of disciplinary reports during the two most recent COVID-19 affected years, racial and programmatic disproportionalities in discipline remain high. We recommend the state consider a larger investigation into how schools are addressing behavioral issues, mental health issues, and school climate issues more broadly, particularly for students in these populations at greater risk of identification and exclusionary discipline.