This blog is written with Sarah Morris, a Graduated Researcher in OEP and former junior high teacher.

Can you imagine how excited eighth-grade students are to enter ninth grade in just a few short months? Some Arkansas students are eagerly awaiting a fresh start in a new building, while others are just ready for something new. As these young minds gear up for this big transition, the choices about which courses they enroll in can influence their future. While ninth grade represents a breath of opportunity for some, in Arkansas, some eighth-grade students may not receive the opportunities they deserve.

Here at OEP, we are now thinking about what kinds of kids get the opportunity to enroll in advanced courses in their ninth-grade year.

Of course all students are different and so are the schools they attend. We can factor in these differences mathematically and then check to see if there are certain types of students being overlooked.

Today, we released our findings of a robust mixed-methods study and policy brief that explored these questions:

- Do some students have a better chance of getting into ninth-grade advanced courses than others based on their background—like their family’s income or their race?

- What things do school counselors consider when deciding which courses ninth-grade students should take in Arkansas schools?

Statistical Analysis:

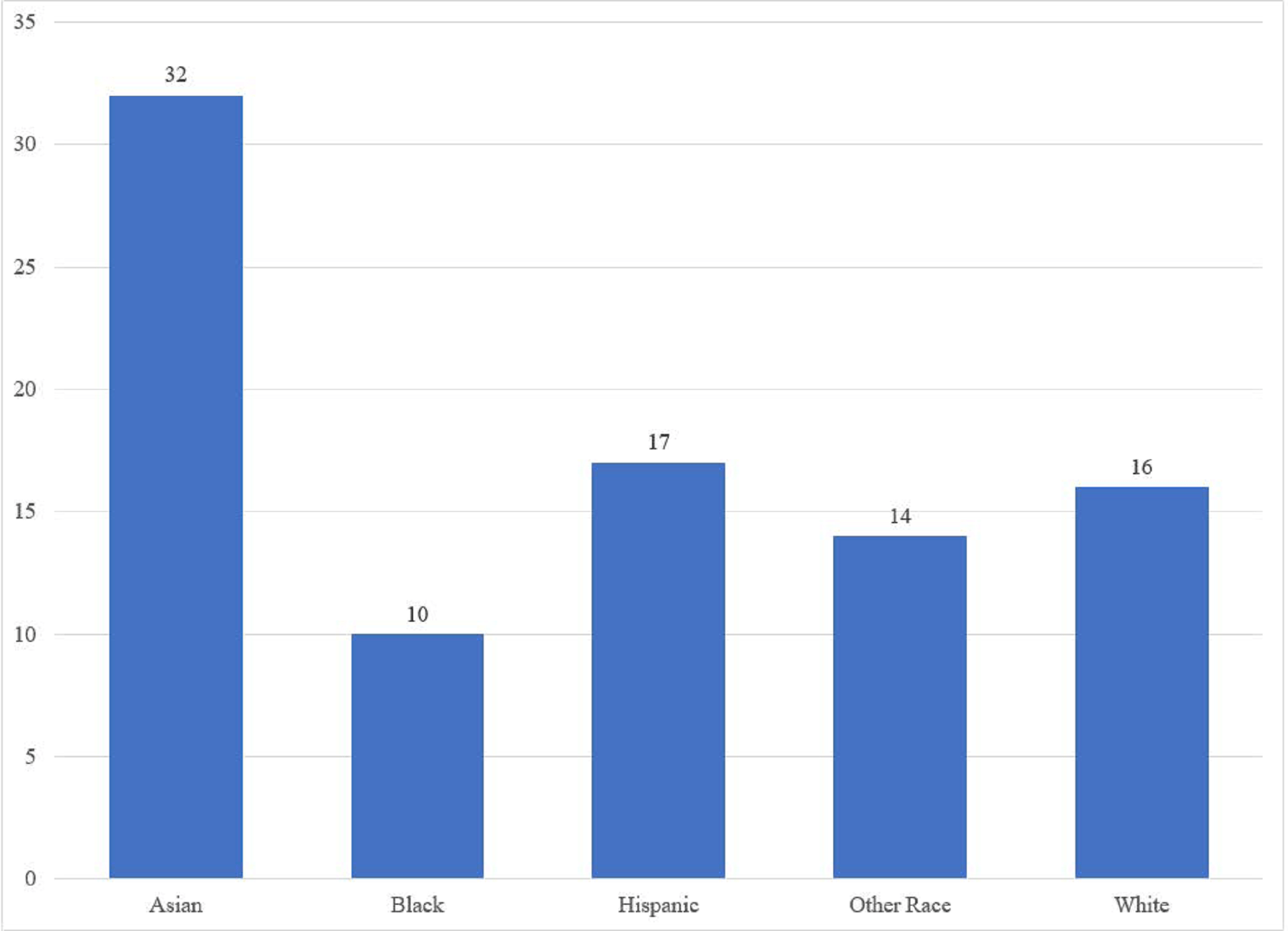

Unfortunately, we do find that some ninth-grade students have a better chance of getting into advanced courses than others, even after accounting for their similar academic abilities. We present Figure 1 to highlight these disparities.

Figure 1: Eighth-Grade Student Likelihood of Enrolling in Ninth-Grade Advanced Courses, Pooled Sample from 2017-2022

This graph highlights more than just simple tabulations of percentages of students enrolling in advanced courses. This graph reflects the likelihoods after we statistically control for differences among students and the schools they attend. This means that of similar-ability scoring students, Black students are three times less likely to enroll in ninth-grade advanced courses compared to Asian students. Black students are the least likely to enroll in advanced ninth-grade courses, despite having the same academic abilities as their peers of other races or ethnicities.

Similar disparities emerge for lower socioeconomic status students. Students who participate in the Free and Reduced-Price Lunch (FRL) program, our proxy for economic disadvantage, are nearly two times less likely to enroll in ninth-grade advanced courses compared to their more advantaged peers. Remember, this after accounting for district characteristics and students’ academic performance on state tests.

Counselor Perceptions:

To explore why these discrepancies in enrollment could be happening, we sent out a counselor survey and conducted 14 counselor interviews. In short, our counselor survey didn’t indicate that counselors were biased against placing lower socioeconomic status students in advanced courses.

Our counselor interviews, however, highlighted the lack of consistency and transparency in how decisions about which students are selected for advanced courses in Arkansas schools. Counselors consider a myriad of factors in ninth-grade course placement, and these factors weren’t associated with district size, FRL compositions in districts, or district regional location. Of the counselors interviewed, most of them believed their school effectively placed students into advanced courses, but some admitted their school had room to grow.

The interviewed counselors noted many hands influencing course placement for ninth-grade students, but the majority of interviewed counselors wished economically disadvantaged students’ parents were more involved in the placement conversations. Some counselors noted that some parents can be too involved in course placement decisions for their ninth-grade students, which can lead to parental desires taking precedence over students’ academic readiness. But this again highlights the lack of consistency in transparent placement systems. Parents should be involved but not too involved; how are they supposed to know?

Recommendations:

Based on these findings, we have a few recommendations. First, students need early exposure to advanced courses like Algebra I, as it could increase interest in advanced mathematics and readiness for future advanced courses. Districts should develop plans to increase access to early Algebra I in seventh and eighth grade.

Additionally, districts should consider implementing a local norm-based placement system that evaluates students’ capacity to succeed in advanced courses against their peers in the same district. Districts could use data to identify high-ability students who have the propensity to succeed in advanced courses with this system, maximizing access to the opportunity. After the local norm-based system is in place, schools should automatically enroll identified students into advanced courses, and parents and guardians can opt to have their student removed. Schools also need a systematic and transparent Plan B process if the advanced class is not working out for the student. These recommendations would streamline the enrollment process and ensure that deserving students are not inadvertently excluded due to lack of parental awareness or involvement, as noted by our counselors.

Overall, districts urgently need more systematic and transparent course placement systems to ensure no student, no matter their race or family income, is denied the opportunity to succeed in advanced coursework.

If you want more information or support in setting up a system like this in your school district, reach out to us at oep@uark.edu. We would love to help!